Thoughts & Recommendations

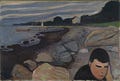

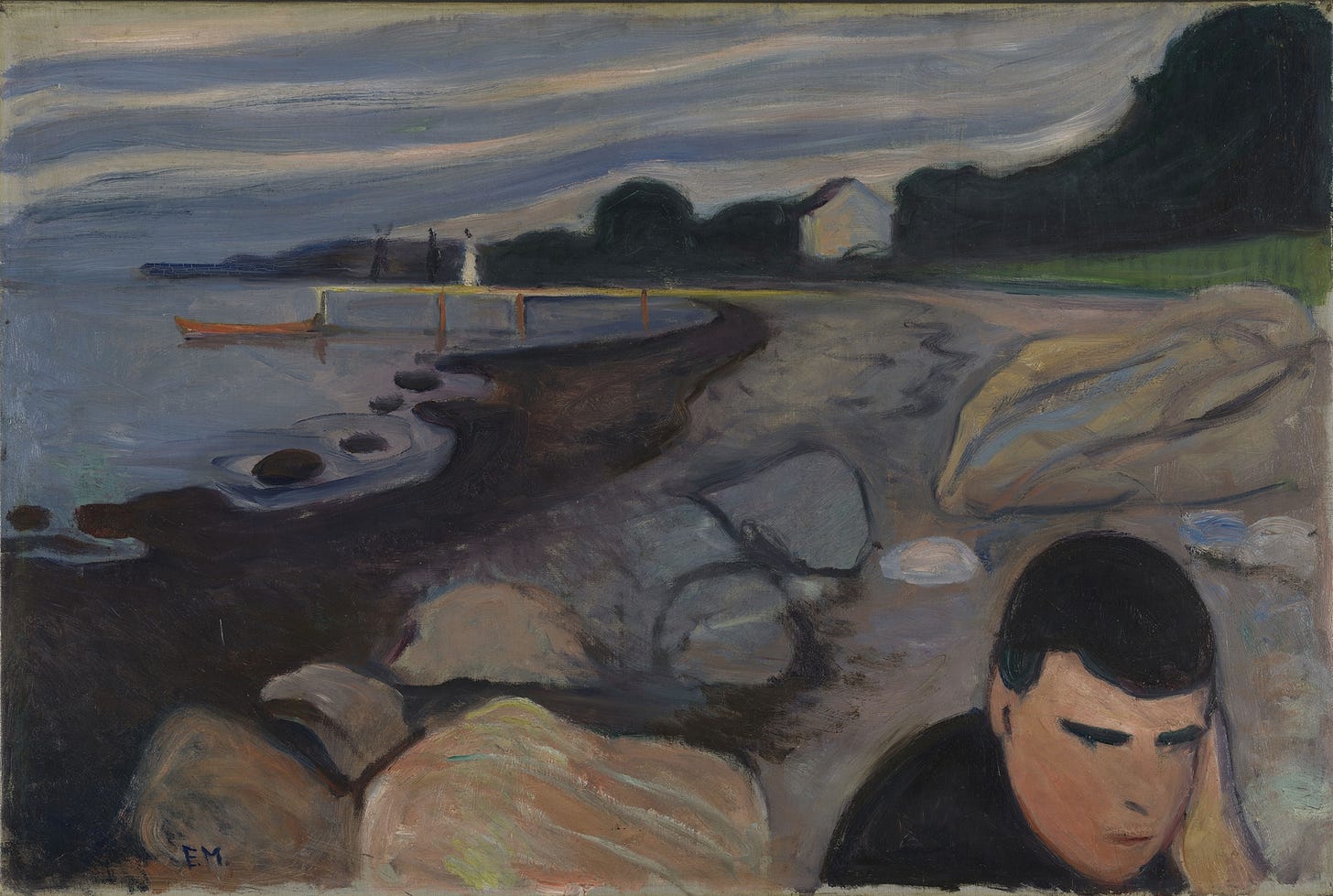

Yesterday, while driving my motorbike home from my morning run at the park, I saw a bird unlike any I’d seen before. It was perched atop a pillar that had been driven into the earth among the rice paddies that define the land behind our house. (The rice paddies that haven’t already been filled with dirt and covered with indistinguishable houses, that is.) I was reminded of the book The Pillar, which includes photos by Stephen Gill and writing by Karl Ove Knausgaard.1 I don’t own the book. It’s one of many things I’ve come across online in the years since moving to Thailand that I’d like to purchase but haven’t. It’s just too much of a hassle, not to mention expensive, trying to get Western goods all the way over here. Sometimes I think about buying those things anyway, sending them to people I know in the US. A few times, I actually followed through on that, including once when I sent Knausgaard’s So Much Longing in So Little Space: The Art of Edvard Munch to an old friend. Whenever I’ve done this, though, it’s just left me feeling selfish. Like I’d given the other person an obligation to deal with. A gift wrapped in and containing my tastes and interests rather than theirs. One that they now must give enough of their time and attention to to at least be able to pretend that they like.

The bird that I saw yesterday, I’m nearly certain, was a white-throated kingfisher. I know this because I looked it up after being reminded of my sighting—and of Gill’s book again—while reading a post by Freddie deBoer this morning that moved me to tears. I’ve chosen to highlight the paragraph below almost at random, as all nine of them hold striking but unique shades of beauty, brutality, or both:

A few weeks ago there was a visitor who could not be said to be to be unnamable - a lone bald eagle, fat and stooped, looking down on the busy veterans memorials below with animal indifference. For a time in my grad school years in Indiana I rented a place right by the Wabash river, a molding one-bedroom in a stooped and constantly-flooding apartments cozied up against a modest inlet, the size of a basketball court. Great Blue Herons ruled the place year-round; I once watched one stalk, spear, and eat a chipmunk. But for five weeks or so in early winter that inlet was ringed with bald eagles, which sat like a glowering parliament in leafless trees and, at odd intervals, would swoop down to take their meals. Fish swim into the inlet and can’t find their way out, so the eating is good. A yellowing sign nearby taught me that there are paddlefish in those waters that break 200 pounds. The eagles seemed content to take smaller game, swooping down and fishing exactly how you would think a bald eagle would fish - a sudden takeoff, homing in with the grace of a limber dancer, a frozen beat of wings, then claws tearing the water’s surface, and thus God makes another ex-fish. But this eagle near home only studied his surroundings; he looked both vigilant and bored. A man walking an obese black lab told me he had come around the year before too, but his vigil felt like a rare and wild moment, and the next day he was gone.

You can read the full piece here.

Here’s the opening of Knausgaard’s description of the book from Gill’s Nobody Books publishing imprint: “A pillar knocked into the ground next to a stream in a flat, open landscape, trees and houses visible in the distance, beneath a vast sky. That is the backdrop to all of Stephen Gill´s photographs in this book.”

He adds later: “I’d never seen birds in this way before, as if on their own terms, as independent creatures with independent lives. Ancient, forever improvising, endlessly embroiled with the forces of nature, and yet indulging too. And so infinitely alien to us.”

Or maybe not so alien?