Something Vague

Now and again, I extract myself from the alluring jaws of my own silence, tune my guitar down a half step, and sit and sing songs. Mostly sad ones. Usually when I’m in a mood.

Invariably, I land on the Bright Eyes song "Something Vague." There’s a lot to like about it. But one lyric in particular gets me every time:

There's a dream in my brain that just won't go away

It's been stuck there since it came a few nights ago

And I'm standing on a bridge in the town where I lived

As a kid with my mom and my brothers

And then the bridge disappears, and I'm standing on air

With nothing holding me

And I hang like a star, fucking glow in the dark

For all those starving eyes to see

Like the ones we've wished on

It's the song's crescendo, and the cinematic images it fills my mind with are somber and poetic. But that's not what gets me. What really does it are the words "And I'm standing on a bridge in the town where I lived / As a kid with my mom and my brothers." As they move from my mouth, my chest gets tight with emotions both potent and illegible. The song veers into a ditch for a second before rising back out unscathed.

There were no bridges in the town where I grew up. Not much water, really. If I go back there via Google Maps now, and then travel one town over, I can sort of stir up a sense of the Ninth Street Bridge that passes over the Des Plaines River. But it holds no real significance for me. What does are these 15 words: "in the town where I lived as a kid with my mom and my brothers." Their significance is their plainness. Their everydayness. Their familiarity. Their subtle dominion in this poem.

Singer-songwriter and voice of Bright Eyes Conor Oberst was born in Omaha, Nebraska in February 1980, the youngest of three sons. I was born two months later, about a seven-hour drive straight east of Omaha on I-80, in the town where I lived as a kid with my mom and my brothers. Both of them older.

This means nothing. I know. And yet it kind of does. And I know that, too. So what even is meaning? Is there ever really any (or none) of it in anything? Or are there only the stories we tell? The ones we make and believe, and the ones we only believe, all of them just different but acceptable variations of make-believe. Is it possible that "we" are just characters on a giant stage suspended in space and spinning, little insignificant creatures being moved about by whatever's beyond the black curtain? Maybe we're not the ones telling the stories at all. Maybe it's the other way around. Maybe the stories are telling us.

"Something Vague" is a song for the darkness that finds its way into troubled minds. It pairs especially well with the darkness that finds its way into cold winters and bones and drinks. It's a song that exemplifies what I mean when I say that listening to sad songs when you're sad is the equivalent of steering into a skid when you're skidding. It's the best way out.

The song is the first from Bright Eyes/Conor Oberst to capture my attention. It arrived to me via a live performance on one of the many dusty-sounding Dax Riggs bootlegs I’d pulled from the primitive tendrils of the early aughts internet. I followed the scent from there to the albums Fevers and Mirrors, Lifted or The Story Is in the Soil, Keep Your Ear to the Ground, and I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning, all of which are now old sonic friends.

Ruminations

The early aughts came and went. Years passed and dark winters turned to bright springs and back again. Everything kept changing and staying the same and I lost track of both Bright Eyes and Oberst. Until one day in 2017, when I found myself listening again to Lifted and I'm Wide Awake, It's Morning, wondering what their creator had been up to since their creation.

I learned that Oberst had some months earlier released his seventh solo album, Ruminations. The day is blurry now. But I remember stark white sun and dark blue curtains in a dim studio apartment. And I remember feeling cocooned there for hours that grew into months with Ruminations, my new old friend.

Like Bruce Springsteen's Nebraska, Ruminations was a standout album for Oberst because of its stripped-down sound and powerful—and at times painful—lyrics. The songs were written in the months following Oberst's cancellation of a tour due to the discovery of a cyst in his brain and his related hospitalization for laryngitis, anxiety, and exhaustion.

Here's how the album is described on Oberst's Bandcamp:

In the winter of 2016, Conor Oberst found himself hibernating in his hometown of Omaha after living in New York City for more than a decade. He emerged with the unexpectedly raw, unadorned solo album Ruminations. Oberst […] recorded all the songs within 48 hours. The results are almost sketch-like in their sparseness: Oberst alone with his guitar, piano, and harmonica; the songs connect with some of the rough magic and anxious poetry that first brought him to the attention of the world, while their lyrical complexity and concerns make it obvious they could only have been written in the present.

That final clause is part of what brings me here today. The morning after publishing my previous essay, Creator-Destroyers, I found myself sitting outside with a cup of coffee and Ruminations. The lyrics all sounded new. Or old, rather. Older, I mean. As though they'd aged. Both with me and with the world. And maybe that's what we really mean by the term timeless. Maybe the dictionary has it all wrong. Maybe timeless isn't when something goes unaffected by the passage of time, but rather when it seems deeply affected by it, so much so that it seems not to be. (Maybe the stories are telling us.) It’s been seven years now since the release of Ruminations, and many of its lyrics still sound like they could only have been written in the present. That’s not really the right way to say it anymore, though, seven years on. A better way might be: many of its lyrics still sound like they could only have been written about the present. Let’s go with that. We can leave the definition of timeless alone (for now).

Near the end of Creator-Destroyers, I wrote this:

I’m not a doomer. But I’m sympathetic to the doom-laden’s distaste for the modern world, and their concerns about the direction our advancements are taking us. I see what the doomers see. It’s just that I also see what the optimists see. And I see enough truth and bullshit in both to stay neutral and uncertain. I see great advancements and great losses that seem to work in unison. I see human nature, and I see us: creator-destroyers, just doing what we do.

At the end of that paragraph, I added a footnote to a lyric from the 2020 Bright Eyes song "Just Once in the World," which my closing words were a nod to. Here's that lyric:

Found the throughline for all humankind

If given the time, they’ll blow up or walk on the moon

It’s just what they do

While sitting outside with Ruminations later, I was struck by another lyric that spoke to some of my feelings about the modern world (and myself). This one in the album's second track, "Barbary Coast (Later)" (emphasis mine):

I don't mind my head when there's room to dream

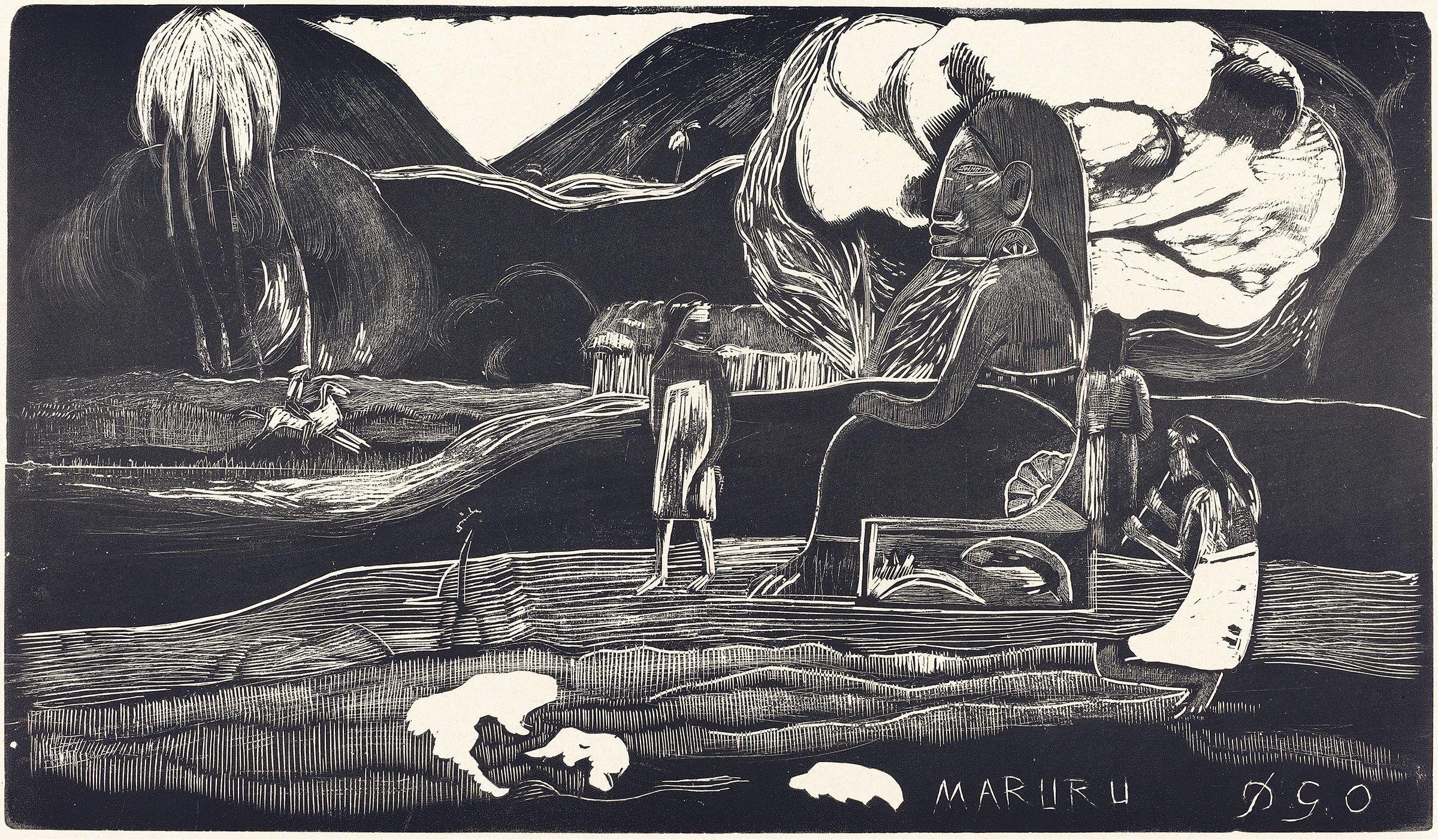

Feel like Paul Gauguin painting breadfruit trees

In some far off place where I don't belong

Tried to lose myself in the primitive

In Yosemite like John Muir did

But his eyes were blue and mine are red and raw

'Cause the modern world is a sight to see

It's a stimulant, it's pornography

It takes all my will not to turn it off

Whether you can relate to those last three lines or not, I suspect you’ll have no trouble understanding the sentiment. We know what Oberst means. And we know what he feels. And well, I happen to relate very much to what he means and feels. My struggle is that I also happen to think that thoughts like the ones below, from

Bhogal on a recent podcast appearance, are true, too:It's easy to blame modernity. Because you don't have to take responsibility for modernity. Because modernity is doing everything for you. Modernity is growing your food. Modernity is keeping you safe from invasions. Modernity is keeping you warm. Modernity is giving you the information that you need to help yourself in pretty much any situation that you could possibly find yourself in. Modernity is a map for you that you can [use to] find your way through anywhere. Modernity gives you pretty much everything. And that allows you the luxury to blame modernity for your problems.

Just before saying this, Bhogal talks about how there seems to have been an increased externalization of the locus of control over the past 40 years or so.1 Breaking the locus of control down further, Bhogal says:

The locus of control is the degree to which one believes that they, as opposed to external circumstances, shape their destiny. So people who have an internal locus of control, they believe that their own decisions dictate what happens in their life. And people who have an external locus of control, they believe that what they do doesn’t really matter because their lives are dictated by what happens in the external world.

So blaming modernity for your problems would be an externalization of the locus of control. Interestingly, Bhogal adds that he doesn’t think people in our distant past had this luxury most of the time.

When you’re trying to survive, you don’t have the luxury of blaming other things. You have to take responsibility for what’s going wrong in your life. But when you arrive in a world like ours where pretty much everything is done for you, you have that luxury. You can now suddenly start blaming everything except for yourself. And that’s why, I think, we have these people who are yearning for this distant past, where everything was—in their eyes—much better. Because they can easily just blame the modern age.

I agree with basically all of that.2 And I would like to think that I have an internal locus of control. I certainly aim to operate as though I do. I believe that I dictate what happens in my life. And when I’m not able to do what I’ve set out to, I see that as an error or failure on my part. One that I need to work to correct or recover from. So my predicament is a little different from the one Bhogal describes. Because I don’t blame modernity for my problems. But modernity is still the framework that I and everyone else alive right now must work within. So it’s not entirely without a role in people’s problems, either, even those with an internal locus of control.

Just as everyone must operate within the parameters of the places and times in which they live. So too must we operate within the parameters of the here and now, for better and worse.

Modernity is a stimulant. But it’s also a sedative. It’s pornography. But it’s also the closest thing we have to decency. It’s enriching. But it’s also depleting. It’s a material luxury. But it’s also a spiritual poverty. It’s our map to everything in life. But it’s also what makes us want to turn life off. It’s the Tree of Knowledge. But it’s also a man, woman, and snake.

Hail modernity!

Damn modernity!

How does one hold both of these thoughts in their head at once?

How does one not?

Counting Sheep

Closing my eyes, counting sheep

Gun in my mouth, trying to sleep

Everything ends, everything has to

Get-well balloon, going insane

Weight of the world, papier-mâché

Gone with the wind, out into nothing

So begin the lyrics to the fourth track on Ruminations, “Counting Sheep.” It’s not my favorite song on the album. Not on the whole. But its lyrics cut deep and dabble in things dark and disturbing, which makes me love it. It’s like a kind of Stockholm Syndrome, only the hostage is a listener and the captor is a song.

Oberst sings:

I'm just trying to be easy, agreeable

I don't want to seem needy to anyone, including you

And my attention turns here to myself and this point that

made in a great essay he wrote about the Underground Man in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground:The Underground Man has an enormous ego. Not in the normal sense, as in someone who thinks they are amazing, but in a more general sense; his ego is extremely inflated, overactive. His ego is basically his entire being. The monologue of the book goes around and around UM’s social standing, his failures, and his negative qualities. He despises himself, he thinks of himself as low and worthless… but you can’t experience these powerful feelings towards yourself without having a powerful sense of yourself. In fact, it is clear that these negative self-conceptions are manufactured in an effort to engorge his ego: he talks about how he makes an effort to be wicked, to be a rat, to get people to notice him, to have some sort of remarkable identity rather than being overlooked or forgotten. This is the power of ego in the Underground Man (and maybe you and me, too).

Oberst continues with what I think is the song’s most compelling verse:

Little ______ drowned in a pool

_____ got killed walking to school

Hope it was slow, hope it was painful

Life is a gas, what can you do?

Catheter piss, fed through a tube

Cyst in the brain, blood on the bamboo

Highway to hell's littered with signs

Every last thing they advertise

I want to buy, I want to sell too

Reader, it is not every day that I will recommend reading the annotations on the lyrics site Genius. But today is a day when I will. Here’s what one contributor wrote about the first three lines:

Describing the deaths of two children, the names are made deliberately unintelligible, as though reflecting media coverage censoring the names to protect the families. But it also makes them interchangeable; these things could happen to anyone.

The following line “Hope it was slow, hope it was painful” seems shocking, a vindictive inversion of the usual hope that death was quick and painless; but from the media’s perspective, the more gruesome the death, the more interest in their coverage. It’s a commentary on the cynical attitude of the media, and the consumers they are catering to.

It could also be taking the perspective that when the subject is a young child, a long and painful life is preferable to an early death. This leads into the following lines, saying ironically “life is a gas” while describing serious medical problems.

Among those following lines is what seems to be an autobiographical reference to one of Oberst’s own serious medical problems at the time. Namely, the cyst in his brain. This is followed by the words “blood on the bamboo,” about which is written:

“Blood on the bamboo” associates the hospital care [of someone in intensive care] with a form of torture wherein bamboo is grown beneath someone who is immobilized (as in a hospital bed) and the new shoots penetrate their helpless body.

Good lord. I have no idea if bamboo torture is what Oberst was actually referring to. Nor had I ever connected those dots before. But the above annotation and subsequent reading I’ve done have made a believer out of me, and I’ll never not think of this while listening to the song or spotting bamboo again. And there’s a lot of bamboo where I live.

In the song’s final verse, Oberst sings:

Early to bed, early to rise

Acting my age, waiting to die

Insulin shots, alkaline produce

Temperature's cool, blood pressure's fine

One-twenty-one over seventy-five

Scream if you want, no one can hear you

Five lines largely about measures (and maintenance and monotony) of good physical health, followed by one about the less measurable contours of poor mental health. Forgetting about this sort of invisible suffering is what I think too often leads us to what David Foster Wallace (RIP) called our “natural default setting,” which he describes in his appropriately famous 2005 commencement speech as follows:

It’s the automatic way that I experience the boring, frustrating, crowded parts of adult life when I’m operating on the automatic, unconscious belief that I am the center of the world, and that my immediate needs and feelings are what should determine the world’s priorities.

He goes on:

The thing is that, of course, there are totally different ways to think about these kinds of situations. In this traffic, all these vehicles stopped and idling in my way, it’s not impossible that some of these people in SUV’s have been in horrible auto accidents in the past, and now find driving so terrifying that their therapist has all but ordered them to get a huge, heavy SUV so they can feel safe enough to drive. Or that the Hummer that just cut me off is maybe being driven by a father whose little child is hurt or sick in the seat next to him, and he’s trying to get this kid to the hospital, and he’s in a bigger, more legitimate hurry than I am: it is actually I who am in his way.

Or I can choose to force myself to consider the likelihood that everyone else in the supermarket’s checkout line is just as bored and frustrated as I am, and that some of these people probably have harder, more tedious and painful lives than I do.

[Please] don’t think that I’m giving you moral advice, or that I’m saying you are supposed to think this way, or that anyone expects you to just automatically do it. Because it’s hard. It takes will and effort, and if you are like me, some days you won’t be able to do it, or you just flat out won’t want to.

But most days, if you’re aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she’s not usually like this. Maybe she’s been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it’s also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider. If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

Not that that mystical stuff is necessarily true. The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re gonna try to see it.

Some of the specifics are dated, but the deeper capital-T Truth remains.

So I will submit to you once again that it is good to steer into the skid of your darker emotions. This is how you get out of them. And it’s how you get others out of the ones that you cause.

Taking the idea further, I submit as well that we should regularly initiate the skids into our darker emotions. And one way to do that is to revisit the songs and albums and ideas that cut deep and dabble in things dark and disturbing.

Salutations

Whereas Springsteen never released the songs from Nebraska that he recorded with the E Street Band, Oberst followed up Ruminations with an album that included full band versions of all of its predecessor’s songs.

Me being me, I can’t help but wonder if there was some indecision involved. Maybe Oberst couldn’t bring himself to choose one over the other. So in the end he just chose both. It’s possible, if not likely, that I’m just projecting, though.

Indecision is my muse, master, middle finger, and middle name. It inspires me, haunts me, defends me, and defines me. But more important than all of that, I think, is that it allows and encourages me to maintain my uncertainty, which might be my only virtue. Nothing stinks as rotten as certainty to me.

The follow-up to Ruminations is called Salutations. It’s a solid album, though I much prefer its sparser ancestor.

By far, my favorite part on Salutations, and my greatest gratitude for its release, arrives in the revised and redemptive second verse on “Counting Sheep.”

Little Louise drowned in a pool

Billy got killed walking to school

Hope it was quick, hope it was peaceful

For more on this and the rise in youth mental illness, see Bhogal’s excellent essay from July, The Pathologization Pandemic.

I’m reminded here as well—for multiple conflicting reasons—of Ted Kaczynski’s thoughts on “surrogate activities” in Industrial Society and Its Future:

When people do not have to exert themselves to satisfy their physical needs they often set up artificial goals for themselves. In many cases they then pursue these goals with the same energy and emotional involvement that they otherwise would have put into the search for physical necessities.

[...]

We use the term “surrogate activity” to designate an activity that is directed toward an artificial goal that people set up for themselves merely in order to have some goal to work toward, or let us say, merely for the sake of the “fulfillment” that they get from pursuing the goal. Here is a rule of thumb for the identification of surrogate activities. Given a person who devotes much time and energy to the pursuit of goal X, ask yourself this: If he had to devote most of his time and energy to satisfying his biological needs, and if that effort required him to use his physical and mental faculties in a varied and interesting way, would he feel seriously deprived because he did not attain goal X? If the answer is no, then the person’s pursuit of goal X is a surrogate activity.